Auctioning Francis Tatton Latour’s Erard harp in Finsbury, London, in 1827

- Lewis Jones

- Feb 28, 2019

- 12 min read

Updated: Mar 1, 2019

In Pedal harps in London music auctions of the 1820s (6 February 2019) I summarised and discussed sales of harps, two of which were at surprisingly low prices, by William Peete Musgrave. A contemporaneous London auction by Messrs Godfrey & Bousfield, of Chiswell Street, Finsbury (the street is situated to the north of the present-day Barbican Centre), yielding a higher price, affords insights into the business of selling and buying musical instruments at the time.

On 31 May 1827 Thomas Arnott, aged 27, pleaded guilty at the Central Criminal Court, London (the ‘Old Bailey’) to the theft of two pianofortes, each valued at £20, one in December 1826, ‘the goods of Muzio Clementi and others’ (presumably made by Clementi & Co.) and one in February 1827, ‘the goods of Sarah Dennis’ (the Sarah Dennis in the court transcript must be Sarah Dennis Goulding (c1766–1843), widow of George Goulding); the brief published transcript of the trial is appended below. How he came by them is not recorded, but it is clear that they had already been disposed of by auction by March 1827.

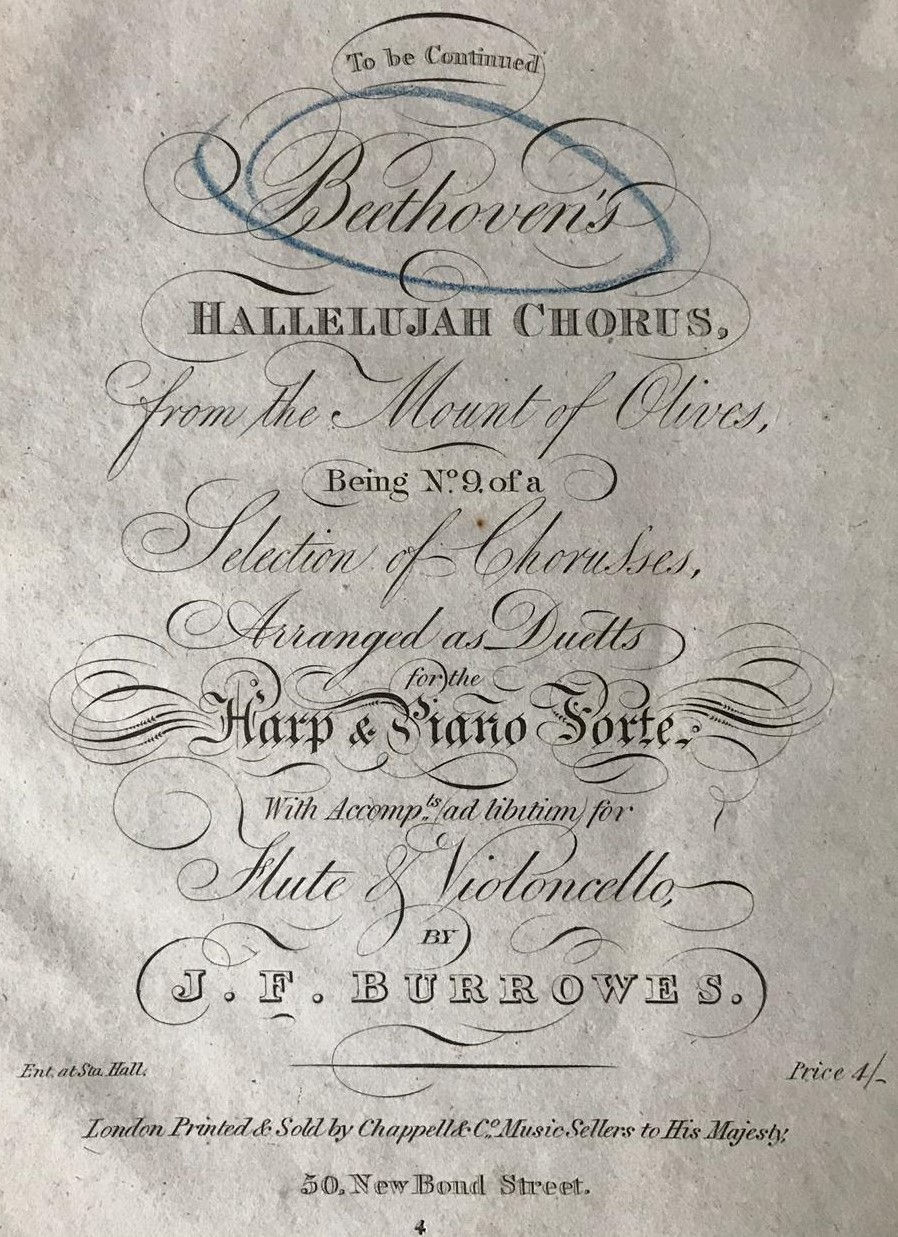

On the same day, Arnott was also tried for the theft of a harp from Frances Tatton Latour (c1766–1845) of [50] New Bond Street, who, from 1810 until 1 June 1826, had been in partnership (also at 50 New Bond Street) with Samuel Chappell, as Chappell & Co.

The hire arrangement

Latour was represented in court by Charles Olivier, his employee – apparently serving as salesman – who stated the value of the harp as 'full £70'. He had hired the harp to Arnott, of 22 Crescent, Euston Square (then a fashionable northward expansion of Bloomsbury, now the forecourt of Euston Station), on 6 March 1827, according to Olivier on behalf of and for the use of his brother, John Arnott, who was said imminently to be expected in London from the country. (It is likely that the Charles Olivier named in the court proceedings is the 'Mr Ollivier, Accomptant, No. 50, South Molton St' who, on 1 June 1826 upon the dissolution of the partnership of Chappell and Latour, was 'empowered by us to receive all outstanding debts'; he, however, signed receipts in that capacity 'Claude' rather than 'Charles'.)

Olivier arranged for a Mr Tucker to carry the harp to Euston the same evening; a note, charging two guineas (£2/2/-) per month for the hire, accompanied it. Apparently about two weeks later, the harp was taken by Thomas Arnott, without John Arnott being aware of it, to the auctioneer in Finsbury, in time to be sold, ‘by public auction in the evening’ of the 29th of the same month, to John Paine, of Cornhill. Four weeks later, on 27 April, only seven weeks after first being hired, the harp was at a Mr Shegan's in Clipston[e] Street, Marylebone. The relationship of Paine to Shegan (perhaps a pronunciation of Sheehan?) and the reason for this further removal are unknown, as is the means whereby Latour traced his missing harp to Marylebone. (It wasn’t unusual for stolen instruments to be deposited with pawnbrokers, but no pawnbroker has been found in Clipstone Street, nor any other business by the name of Shegan/Sheehan/Sheen.) The case was heard in court a further month later, Paine appearing as a witness. It seems unlikely that even the initial monthly hire payment, presumably due in the first week of April, was ever made – it was not mentioned in court by Olivier.

According to the printed court proceedings, Paine stated that the harp he had bought, which was actually presented in court and sworn to, was by ‘Hurrard’ – obviously a mistranscription of ‘Erard’. That Arnott had left it to Olivier to select a suitable harp for his brother suggests a lack of expertise or of real interest. If £70 is the price for which Latour would have sold it, the harp might have perhaps been a second-hand one, previously hired, or perhaps a newer single-action one. (At £2/2/-, the monthly hire charge was 3% of the value of the instrument.) On the other hand, £2/2/- is only marginally less than £2/4/6 per month, the rate at which Clappell & Co., from 18 June 1821 until January 1822, had hired an unidentfied but presumably excellent harp to King George IV (I will shortly present here a summary of references to harps, their strings, and associated services in the Privy Purse Accounts for music).

The auctioneer

By 1827 Robert Godfrey had been established in Chiswell Street, initially alone, for at least five years. An advertisement in The Morning Post on 9 October 1822 confirms his address as 73 Chiswell-street, Finsbury Square, and states the nature of his business at that time:

‘HOUSEHOLD FURNITURE, LUMBER, FIXTURES, &c. [...] The Public is respectfully informed, that a liberal price and immediate cash is paid for large or small quantities in town or country, avoiding the expense and inconvenience of an Auction, by applying to Robert Godfrey Auctioneer, &c., 73, Chiswell-street, Finsbury-square.– Furniture, Fixtures, and Effects in general, valued on equitable terms.’

By 21 May 1825 (advertisement in The Times) he had moved to no. 35, on the opposite side of Chiswell Street, and his continuing there is confirmed by advertisements in The Morning Post (3 November 1825) and The Morning Chronicle (31 October 1826).

By1827 Godfrey was in partnership with Richard Pritchett Bousfield, but their partnership was brief; by the date of the trial it had been sundered.

The trial

Asked in court whether he knew that the harp was worth as much as £70, Godfrey – a valuer by trade – declared that he did not. He seems to have been defensive about his conduct: when initially asked by Thomas Arnott whether he would sell an instrument – ‘something in the musical line’ – for him, he had been persuaded, according to his own account, by being reminded of having previously sold some furniture for a ‘Mrs. Arnott’, the defendant’s mother; he ‘recollected the circumstance’ well enough – she ‘kept a very respectable private house’. Arnott had ‘represented himself as a musical dealer’. Asked whether he had taken the trouble to see where the defendant lived, Godfrey said that he had not: ‘I knew nothing of him, except for selling goods for him at my auction-room. I had sold two instruments for him before, one of Golding’s and one of Clementi’s.’ These, presumably, were the two pianofortes to whose theft Arnott admitted.

Godfrey claimed in court that he would have preferred to have sold the harp in a ‘respectable’ sale – one with a printed catalogue – through which, he had advised Arnott, they would have achieved the best price; but he did not convey that the £32 realised had been disappointing or unexpected. Arnott was presumably unwilling to wait for the printing of the next periodic catalogue because he wanted a quick sale, before hire payments became due and Latour pursued him. Godfrey was, nonetheless, at pains to point out the respectability of his evening auction, which had been ‘advertised in The Times'. Unlike Musgrave, who accumulated large groups of instruments for sale in orderly, occasional central-London music auctions, Godfrey, who held regular weekly mixed auctions in Finsbury, had ‘sold many [instruments] without a catalogue.’

In contrast to the harps auctioned by Musgrave, whose immediate provenance is unknown, that sold by Godfrey & Bousfield had just come from the West-End shop of the ‘Pianiste to His Majesty’ (King George IV).

Chappell & Co., Latour’s partners until 1 June 1826, had advertised that he, with Johann Baptist Cramer, personally selected and approved each instrument they offered for sale; so even if the harp had previously been out on hire, it is likely to have been in good working order. This, together with its being an Erard (the make most esteemed in aristocratic circles) rather than a less conventional Dizi double-action (sold by Musgrave on 13 December 1826 for £21) or an Erat (sold for £17), might account for the higher sale price achieved by Godfrey; nonetheless, the court was surprised that the Erard had been sold for so little.

Godfrey’s account of their acceptance of the harp at Chiswell Street lacks clarity and is somewhat contradictory. One senses that he was discomfited appearing in court; he sought to distance himself and to share any blame with his partner:

‘I found the harp on my premises at nine o’clock – I believe Mr. Bousfield took it in – it came about six in the evening – it was not dark– it was darkish. [Sunset in mid-March in London would have been at about 6.00 pm.] I saw the prisoner there and gave him 12l. on it;’ […] ‘we sometimes sell by printed catalogues – this was not in a printed Catalogue [sale]. I told him at the time, that till we had a respectable sale, we should not get a good price. I have an auction every week – it was regularly advertised.’

Upon accepting the harp for sale, Godfrey had advanced £12 (37.5% of the eventual hammer price) to Arnott. It is not clear whether this was a common practice (the terms in Musgrave’s printed catalogues, for example, do not mention it), and he did not explain to the court how that amount was determined. Perhaps Arnott, in need of money, persuaded him to make an exceptional payment. In answer to the jury Godfrey reported that the sale ‘duty’ was normally, ‘at respectable sales’, paid by the seller; it amounted to 32s (5% of the hammer price) and in this case it was included in the £4 (12½%) deducted by Godfrey from the hammer price for ‘auction duty, commission, and trouble’. Thus Arnott received £28 net.

Aftermath

Thomas Arnott was found guilty of grand larceny and was deported for seven years. His brother, John, did not attest to the claim, related at the outset of the trial by Olivier, that Thomas had initially pretended that the harp hired was intended for his use while he visited London from Shrewsbury. Thomas, protesting that he was ‘a respectable individual, with whom [he claimed] the prosecutor [Olivier] was acquainted’, denied in court that he had obtained it for his brother’s use, or that he had even used his name. He claimed to have ‘lost the note’ which defined the hire terms.

It is difficult to reconstruct the chronology of events from Arnott’s plea. Having been ‘totally out of employ for twelve months, and much reduced’, and then ‘arrested for £65’, he had been ‘induced, by the persuasion of a friend, to dispose of this instrument [i.e. the harp present in court] to relieve’ his financial situation. Although we can’t be certain whether this sum of £65 related in part to monies owing on other instruments (including, perhaps, the Clementi and the Goulding) he had obtained from shops or elsewhere (it appears not to pertain directly to the harp itself, which had only recently then been hired), or whether it was another debt, he claimed to have been ‘released [from the debt] the very night [the harp] was sold’. (Given the shortfall between £32 and £65, this is difficult to account for.) Arnott claimed, in justification of taking the harp to auction, to have been ‘assured by a friend that [the harp] should be purchased [perhaps, by arrangement, by the same friend] and [that the friend] would [then] give [Arnott] his acceptance for it’. Was Arnott perhaps let down or deceived in this connivance by his friend? There was no suggestion in court that Paine, who seems unwittingly to have bought a stolen instrument, was implicated.

Although only ten weeks had elapsed between the auction and the trial, Godfrey was, according to his court testimony, by the time of the trial ‘formerly in partnership with Mr Bousfield’. The actual date of dissolution is confirmed in The London Gazette, Part 1, 4 May 1827 (London: Neuman), p. 994:

‘NOTICE is hereby given, that the Partnership between the undersigned, trading under the firm of Godfrey Bousfield, of Chiswell Street, in the County of Middlesex, Auctioneers and Appraisers, was this day dissolved by consent.– Dated this 23d day of April 1827.

Robert Godfrey. Richard Pritchett Bousfield.'

Whilst we might speculate about relations and connections between Thomas Arnott, his persuasive ‘friend’ (if real), Paine, Shegan, and others, and about the path taken by the harp in relation to those individuals between the auction (29 March) and arriving at an unknown date at Shegan’s, it is certain that by the time Olivier inspected the harp at Shegan’s (27 April), the business partnership had been dissolved for four days. It seems likely that the experience, for Godfrey and Bousfield, of investigation by the authorities of their having sold a succession of three stolen instruments, and the consequent prospect of appearing in court, precipitated a rupture from which their partnership could not recover. Presumably Godfrey, as the partner of longer standing who had negotiated the arrangement for sale with Arnott, was bound to represent their former concern before judge and jury.

Although advertisements in The Morning Chronicle and The Morning Post confirm Godfrey’s continuing presence at 35 Chiswell Street on 2 June 1827, three days after the trial, by 30 August 1827 an advertisement in The Times announced a new partnership on the same premises: Bousfield & Phillips: ‘[…] For further particulars, apply to Bousfield and Phillips, auctioneers and house agents, 35, Chiswell-street, Finsbury-square.’ (There is no connection with the well-known firm of auctioneers founded in 1796 by Harry Phillips, a former clerk to James Christie.)

Bousfield & Phillips seem to have concentrated on estate agency, though the newcomer, Richard Phillips, later became a noted coal merchant. Bousfield already had a complex business history: sixteen years earlier, on 1 May 1811, The London Gazette, Part 2 (London: Neuman), p. 1359, listed ‘Richard Pritchett Bousfield, formerly of Wilson Street, Finsbury Square, and late of Cross Street, Finsbury Square in the County of Middlesex, Silk Broker’, as a bankrupt Prisoner in the King's Bench Prison in the County of Surrey; and his partnership with Phillips, according to the London Gazette, Part 2, 14 August 1829 (London: Neuman), p. 1532, was brief:

'Notice is hereby given that the Partnership heretofore subsisting between us the undersigned, Richard Pritchett Bousfield and Richard Phillips, of Chiswell-Street, in the County of Middlesex, Auctioneers and Appraisers, trading under the firm of Bousfield and Phillips, was this day dissolved by mutual consent.–dated this 11th day of August 1829.

R.P. Bousfield.

Rd. Phillips.'

This was confirmed in The Morning Post and The Standard on 15 August 1829. Phillips stayed on at 35 Chiswell Street, but such was the state of the market that, despite diversification as ‘Auctioneer and Appraiser, Dealer and Chapman’, his bankruptcy was announced in The London Gazette, Part 1, 9 May 1834 (London: Neuman), p. 848.

Transcript of the trials

THOMAS ARNOTT. 31 May 1827

1151. THOMAS ARNOTT was indicted for stealing, on the 27th of December, 1 pianoforte, value 20l., the goods of Muzio Clementi and others. Also, for stealing, on the 1st of February, 1 pianoforte, value 20l. , the goods of Sarah Dennis.

To which indictments the prisoner pleaded GUILTY.

THOMAS ARNOTT. 31 May 1827

1152. THOMAS ARNOTT was again indicted for stealing, on the 6th of March, 1 harp, value 70l. , the goods of Francis Tatton Latour.

MR. ANDREWS conducted the prosecution.

CHARLES OLIVIER. I am in the employ of Francis Tatton Latour, a musical-instrument dealer, of New Bond-street. On the 6th of March, the prisoner came to hire a harp – he left it to me to select a good one; he gave his name, Mr. Arnott, No. 22, Crescent, Euston-square, and said the instrument was for the use of his brother who he expected in town from Shrewsbury, in a few days. I know we have a customer of that name at Shrewsbury – but do not know his person. I delivered an instrument to Tucker, to carry it there that evening; I did not see it again till the 27th of April, when it was at Mr. Shegan’s [perhaps Sheehan?], Clipston-street, Mary-le-bone – it is worth full 70l.; he only hired it.

Prisoner. Q. Did not you send a note with it, addressed to me?

A. No; it was addressed to Mr. Arnott – not to Mr. Thomas Arnott.

ROBERT GODFREY. I am an auctioneer. I was formerly in partnership with Mr. Bousfield. I live in Chiswell-street, Finsbury. I knew the prisoner first twelve or eighteen months ago – he then lived in the Crescent, Euston-square, I believe; I knew nothing of him as a resident there, but he came to me in Chiswell-street, and said he had an instrument to sell, and would I sell it – he said “Mr. Godfrey, you recollect buying some furniture of my mother.” I said, “Who was she?” he said “Mrs. Arnott,” he said he had something in the musical line to sell. I looked into my book and found the name, and recollected the circumstance.

Q. You never took the trouble to go and see where he did live?

A. No; I knew nothing of him, except for selling goods for him at my auction-room. I had sold two instruments for him before, one of Golding’s and one of Clementi’s – his mother kept a very respectable private house – I bought some furniture of her; the prisoner represented himself as a musical dealer[.] I found the harp on my premises at nine o’clock – I believe Mr. Bousfield took it in – it came about six in the evening – it was not dark – it was darkish. I saw the prisoner there and gave him 12l. on it; it was sold on the 29th of that month by public auction in the evening, for 32l., to Mr. Paine. I paid the prisoner 16l. more; 4l. was the auction duty, commission, and trouble – the duty was 32s.; we sometimes sell by printed catalogues – this was not in a printed Catalogue. I told him at the time, that till we had a respectable sale, we should not get a good price. I have an auction every week – it was regularly advertised.

Prisoner. Q. Did you ever sell any instrument besides these for me?

A. No; only these three, but I have sold many without a catalogue.

COURT Q. Have you not heard that this was worth 70l.?

A. I did not know the value.

JURY. Q. Who generally pays the duty?

A. The seller always does at respectable sales – it was advertised in the Times.

JOHN PAINE. I live in Cornhill. I bought a harp, by Hurrard, at this sale. I shewed the same afterwards to Mr. Olivier. (Property produced and sworn to.)

JOHN ARNOTT. I am the prisoner’s brother. I never authorized him to apply for this instrument for me.

Prisoner’s Defence. I solemnly deny that I ever obtained it for my brother’s use, or even used his name – but as a respectable individual, with whom the prosecutor was acquainted. A note accompanied it charging me two guineas a month for the hire – if it was for my brother’s use, why send a note to me – I have lost the note. I had been totally out of employ for twelve months, and much reduced. Being arrested for 65l. I was induced, by the persuasion of a friend, to dispose of this instrument to relieve me; I got released the very night it was sold. The law I believe, requires I should have a felonious intent at the time; I was assured by a friend that it should be purchased and he would give me his acceptance for it.

GUILTY. Aged 27.

Transported for Seven Years.

Source

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0),

May 1827, trial of THOMAS ARNOTT (t18270531-138).

May 1827, trial of THOMAS ARNOTT (t18270531-139).

Comments