Pairs of harpers and pipers

- Cary Karp

- 2 days ago

- 8 min read

The following essay initially appeared on the author’s personal blog at https://loopholes.blog/. All references to previous posts are linked to that site.

A late-18th century production of the ballet pantomime Oscar & Malvina, at Covent Garden in London, featured a duet played on the union bagpipes and pedal harp. It is considered from the perspective of the pipes and piper in the preceding post. The present text adds further detail to this and widens the focus to include the harp and harpers. Here is a snippet from the playbill for the 20th performance of the premiere season, on 14 December 1791:

A New Grand Ballet Pantomime (taken from OSSIAN) called,

OSCAR and MALVINA:

Or, The HALL OF FINGAL

…

The Harp and Pipes to be played by Mr. C. MEYER and Mr. COURTNEY

Denis Courtney was introduced in the earlier post, as Charles Meyer will be further below. The 12 May 1792 performance of another Covent Garden production (Inkle and Yariko) included an afterpiece titled, The Irishman in London. Among the features listed in its playbill was “a Duetto on the Union Pipes and Harp by Courtney and Weippert.” John Weippert replaced, or alternated with Meyer in Oscar & Malvina, which ran for decades. A press review of the 31 May 1792 performance notes:

Oscar and Malvina, May 31, went off remarkably well, though Courtney, the piper, was not present. Weippert, with his harp, undertook the whole piece by himself, with wonderful execution and taste.

Courtney died in 1794 and gave his last stage performance on 2 June of that year, together with Weippert. They were advertised as playing “several much admired Pieces on the Union Pipes and Pedal Harp.” That is the type of harp one would expect to find at a metropolitan European concert venue in the late-18th century, albeit in its “single-action” form; the “double-action” (modern) instrument was a while in the offing. The pedal harp’s technical resources would also have been a prerequisite for Weippert’s solo rendition of the rondo in Oscar & Malvina.

The only attested use of the term “union pipes” during Courtney’s lifetime was his own (discussed at length here). This raises a question about the Irish bagpipes in the description of his funeral procession. It was “preceded by two Irish pipers, one of whom played on the Union-pipes used formerly with such wonderful effect by the deceased.” The instrument played by the other piper will be considered after a review of the development of the pedal harp, and biographical details of selected players.

The single-action pedal harp was invented in Bavaria at the end of the 17th century by Jakob Holtzbrucker. He based it on the Central European “hook harp,” of which the definitive feature is a simple device placed next to each string. When engaged, it shortens the length of that string and raises its pitch by a semitone (an approach ultimately restored in the present-day lever harp). Doing so requires lifting a hand from the strings, potentially interrupting the flow of the performance.

Holtzbrucker’s mechanism (described here) obviates this concern with one pedal for each note in the seven-step diatonic scale, effecting a semitone shift in the pitch of all corresponding strings; the C pedal changes every C to C♯, the E pedal every E to E♭, etc. (The later double-action pedal harp added a third position to each pedal allowing, for example, all G strings to be set to G♭, G♮, or G♯.)

Other harp makers enlarged the instrument and modified the mechanical details of how the strings were shortened. The following video demonstrates a design of Henri Naderman on a harp that he built in Paris in 1775, with a performance of a sonata composed by Philippe-Jacques Meyer.

Meyer was born in Strasbourg and professionally active both there and in Paris. While still in his hometown, he took lessons on the pedal harp from Christian Holzbrucker, the nephew of Jakob Holzbrucker. Meyer relocated to London in 1784 where he changed his given name to Philip James. He composed for the pedal harp and wrote the earliest known instruction book for it in 1763 (providing the banner image for the present post).

The C. Meyer who played the harp in Oscar & Malvina was all but certainly Philip James’s son, Charles. The two played side-by-side in London. An advertisement for a concert at the Theatre Royal in Dublin, on 31 July 1792, includes “a sonata on the pedal harp by Mr. Meyer.”

John Ehrhardt Weippert was born in Germany and became a naturalized British citizen in 1801. A review of a concert held on 3 July 1793 states that he was “confessedly the first player in the Kingdom on the pedal harp.” As did the senior Meyer, he composed for and performed on it, and published an instruction book titled The Pedal Harp Rotula, and New Instruction for that Instrument, in 1800. He accompanied pipers other than Courtney, including P. O’Farrell, who enters into this narrative more fully three paragraphs below.

Detailed biographical information about Weippert is online here and here. The latter source includes an indistinct reproduction of an image “Drawn from life by R. Newton” in 1797, of “The Celebrated Mr. Weippert in the Ballad of Oscar and Malvina.” A bit more detail can be seen in the printed edition, copied below. (I'll replace it with a higher-resolution facsimile of the original work that is currently on order, upon receipt.)

As stated in the playbill cited at the outset of this post, the production was “taken from Ossian” – an alleged ancient poet whose mythos and oeuvre have since been determined to have been concocted in the 18th century. Many images of Ossian portray him playing a harp, often while singing to Malvina, the widow of his son Oscar. The instrument commonly appears in a variety of imagined archaic forms.

A 19th-century oil painting by Giacomo Trecourt is one of the few showing a harp based on a real model. This is an Italian design believed to have developed into the hook harp in the mid-17th century. It is seen here to the left in comparison with the drawing of Weippert in the stage production.

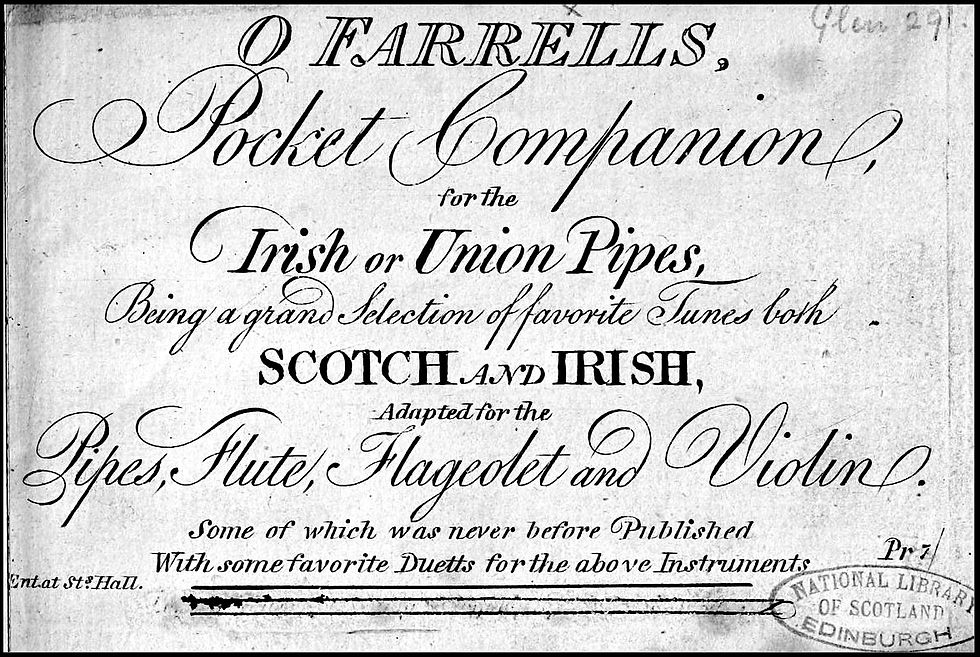

Similarly comparing bagpipes, a portrait of Courtney on the Oscar & Malvina stage (included in the preceding post) was apparently cloned by one of the pipers who succeeded him. This was the O’Farrell well known for his collections of Irish bagpipe tunes. He published the first in London at an unknown date estimated by the renowned early-20th-century compiler of Irish tunes, Francis O’Neill, to be ca. 1797–1800.

The central images of Courtney and O’Farrell show significant differences in the structure and playing position of their instruments.

Courtney holds the drones above his left arm. This would rule out the use of regulators – a characteristic element (demonstrated below) of what would unambiguously become the Irish bagpipes – but none are present. O’Farrell’s pipes are shown in decidedly less convincing detail but a three-keyed regulator does appear to be near his right hand. The regulator would rest on his leg with the drone, if the playing position were rendered more accurately.

Courtney’s chanter is the longer of the two by enough to suggest that he was unlikely to have closed its lower end against his leg. This was, and remains, a distinctive technique on union pipes with regulators (now called uilleann pipes). It can therefore reasonably be posited that O’Farrell was playing the differentiating shorter chanter.

Drones supported above the arm permit ambulatory use and the union pipes shown with Courtney were likely the type played in his funeral procession (now called pastoral pipes). O’Farrell’s variant is less amenable to being played in a non-stationary situation. The two forms could otherwise have been recognized as separate by the chronicler of the procession, but it is also possible that the second Irish piper in it played the warpipes (the national counterpart to the Scottish Highland bagpipes).

O’Farrell published his next collection ca. 1806, “for the Irish or Union Pipes.” The instruments to which he adapted the tunes in both of his books could as easily be found on the roster of a present-day traditional Irish performance, or casually gathered at a pub session. (The historical path from tin whistle to flageolet and back to tin whistle is detailed in another earlier post.)

The type of harp that O’Farrell additionally included on the cover of his Collection of Irish National Music is a matter of some speculation. He may have been prompted by the focus on the centuries-old wire-strung Irish harp underlying the Belfast Harp Assembly in July 1792. Edward Bunting transcribed the tunes played there, concentrating on the melodies.

The older harpers’ approach to their accompaniment is indicated in Bunting’s initial notebooks (discussed here) but he published the upshot extensively “adapted for the Piano-Forte.” The first of three volumes appeared in 1797, possibly in time for O’Farrell to have taken notice of it while still preparing his own first publication. The suitability of the waning wire-strung harp to the kind of tunes in his collections can be assessed in the next video.

The gut-strung pedal harp is an obvious alternative. Meyer’s 1792 concert performance in Dublin has already been cited. Concerts on Irish and Welsh harps had long been advertised there prior to that event. A “German harp” was added to the list in 1774. It is not certain that this was a pedal harp but its ascendency was highlighted soon thereafter in an advertisement for a concert to be held on 14 December 1775, “for the benefit of Mr. Jones, who will perform several select pieces on the celebrated Pedal Harp.”

O’Farrell may simply have intended his first collection for any available type of harp. He listed it next to the piano, indicating awareness of the trend fostered by Bunting, toward the two instruments being treated as equivalent in the transcription of traditional Irish music intended for use outside the contributing communities. He removed both from the list on the cover of his second publication, perhaps suggesting that he felt a collection of tunes without any accompaniment was best presented for instruments intended primarily for melodic use. Alternatively, he may initially have been targeting the wire-strung Irish harp and subsequently come to feel that it was no longer relevant.

The rondo for the union pipes and harp in Oscar & Malvina is based without mention on the traditional Scottish tune Kempshot Hunt. The earliest known edition of the score for the stage production includes a second piece labeled explicitly for pipes and harp. It is again untitled, but is the tune Maggie Lawder that Courtney featured in the concert at Mason’s Hall in London on 14 May 1788, where he introduced the union pipes.

Last Night Mr. Courtney introduced a new species of music to the public, called the Union Pipes, being the Scotch and Irish Bag-Pipes united; and he performed Maggie Lawther, with its variations, on it with great success.

Many printed versions of Maggie Lawder include sets of variations. Courtney used the tune as the centerpiece of his performances on the union pipes for the duration of his career, with his own variations as the highlight. This presumably explains why it was included in Oscar & Malvina. The score only presents the basic tune, which may indicate that the pipers were given free reign to add whatever variations they wished. On the other hand, elaborate cadenzas are notated in the Kempshot Hunt rondo (which O’Farrell carried into his 1806 collection as Oscar & Malvina (Set for the pipes), concluding it with the tune).

Either way, Maggie Lawder is presented differently from all other instrumental pieces in the cited score. There are separate parts for the two instruments rather than a piano reduction. As is customary when writing for the harp, a treble staff is provided for the right hand, and a bass staff for the left. This also permits a piano to be substituted for the harp and vice versa, unless – as is not the case here – the writing is technically specific to only one of the instruments.

The Kempshot Hunt rondo appears in a piano reduction.

While the pipes clearly kept to the melody, the harp can have played both parts, pausing or shifting to pure accompaniment during the piper’s virtuosic flares, such as the cadenzas mentioned above (discussed further in the preceding post). This leads to the broader topic of historical differences between how a harp or keyboard was used when accompanying a separate solo instrument, and for self-accompaniment while also playing the melody (examined in yet another earlier post).

To conclude the present outing, here is a demonstration of the overlapping roles illustrated in the preceding example, in a large-venue stage performance on the contemporary Irish harp and bagpipes.

Comments